How Andy Grove's Writing Formed The Basis For Modern-Day Startup Culture

Tech leaders of today leaned on the writings of Andy Grove to build forward-thinking cultures that reshaped our world.

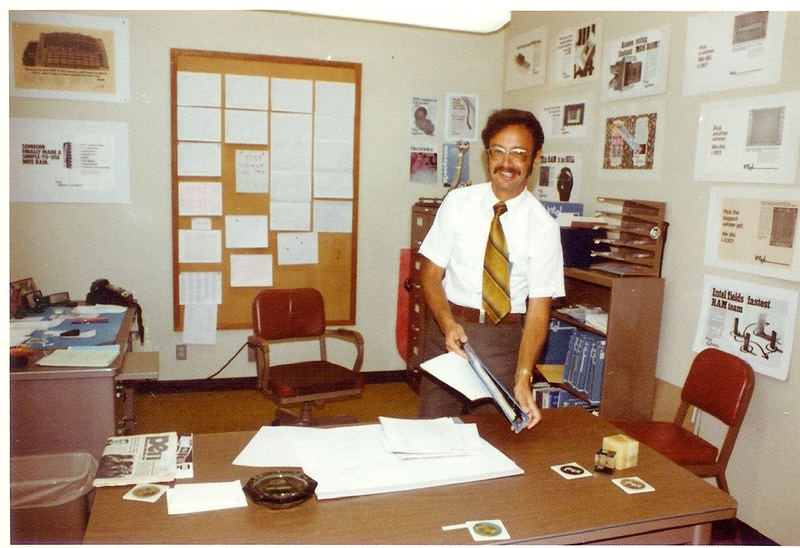

When Andy Grove, former CEO and cofounder of Intel, passed away in 2016, the outpouring of tributes to his memory from the tech world's leading CEOs, such as Tim Cook and Bill Gates, showed just how appreciated his teachings were.

The further you look into the leadership tactics of some of the most successful tech companies of our generation, the more apparent Grove's influence becomes.

In his books High Output Management and Only the Paranoid Survive, Grove laid out the elements of the management strategies that propelled Intel from a tiny startup to the most successful tech company of its day and then led the company through a drastic realignment in the 1980s.

The ideas Grove made accessible to the world through his writing were readily adopted by leaders for years to come to come. With his ideas, these leaders built cultures within their own companies that enabled them to thrive in the fast paced world of tech.

Paranoia As A Motivator

One of the most enduring pillars of Grove's legacy is his idea that paranoia can be a valuable tool for an executive. Prior to Grove, no one touted paranoia as a trait worth generating in your business, but that all changed when he published Only The Paranoid Survive.

Since then, leaders such as Bill Gates, Michael Bloomberg, and Jeff Bezos have made their particular blend of paranoia central to their company cultures and used it to drive their companies to success.

For Grove, paranoia was a central feature of his life from childhood on. Having survived Nazi occupation of Hungary, followed shortly after by Soviet occupation, Grove's survival depended on expecting and preparing for the worst at all times. Being born into a Jewish family, Grove had to be in survival mode constantly. That meant hiding out with a Christian family and adopting a Christian name. Grove's mother reminded him that forgetting to use his Christian name could be disastrous.

Intel employees, similarly, recount that Andy viewed competition as Soviet tanks coming down the road. His famous slogan, “Only the paranoid survive,” became a common mantra within the company, and it became so central to Grove's management philosophy that he wrote a book titled Only The Paranoid Survive. On the first page, Grove explains the basic reason why paranoia is so important in business: because someone else will always want to take what you have, whether that's market share or capital.

“Business success contains the seeds of its own destruction,” he writes, “The more successful you are, the more people want a chunk of your business and then another chunk and then another until there is nothing.”

One of the moments at Intel where Grove's thinking about paranoia came in use was in the 1980's when Japanese manufacturers started cutting into Intel's profits by making their products cheaper and cheaper. Grove foresaw a future where Intel would eventually be drowned out by these manufacturers and, instead of waiting for that to become a reality, decided to change course and abandon the very product that had built Intel into a global behemoth. Within the company however, resistance to change was heavy.

At Intel, the belief that the company lived and breathed memory had ascended to the point of “religious dogma.” But their customers had already seen how short-lived their dominance of the memory space would be in the future:

“In fact, when we informed them of the decision [to switch to microprocessors],” Grove wrote, “some of them reacted with the comment, 'It sure took you a long time.' People who have no emotional stake in a decision can see what needs to be done sooner.”

For Grove, constant paranoia about your business's odds of survival given the constant onslaught of competitors enabled by the free market was essential to “seeing what needed to be done.”

Since then, CEO's have openly and readily espoused Groves ideas on paranoia in business. Although not mentioning Grove directly, Michael Bloomberg closely mirrored Groves thoughts in his book Bloomberg by Bloomberg when he wrote, “Every day at Bloomberg, we face challenges that jeopardize our comfortable life. We constantly have to fight competitors trying to take food out of our children's mouths. And then there are start-ups that want to destroy everything we've built.”

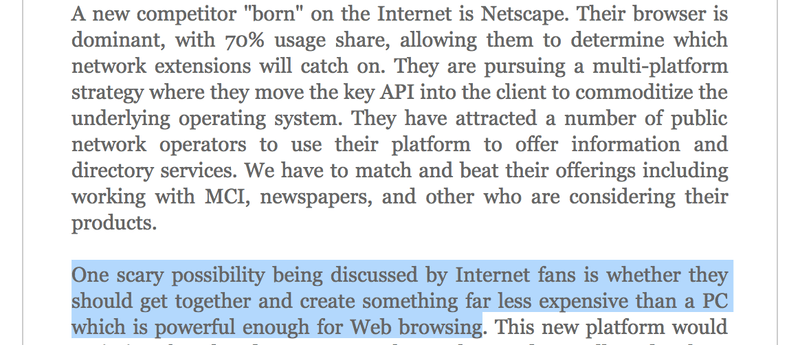

In 1995, Bill Gates wrote a paranoia-inflected memo of his own to all Microsoft employees. In the document now known as the “Internet Tidal Wave” memo, Gates reflects on how disruptive the internet will be and how easy it could be for their competitors to take advantage of its power to make Microsoft insignificant.

One competitor Gates calls out in particular, Netscape, was, at the time, only at ~$5 million in revenue vs. Microsoft's $8 billion. Even though the the company was only a small fraction the size of Microsoft, Gates imagined a future where they could overtake and even commoditize Microsoft. No competitor was too small to be considered a threat. If they had a good product in the internet space, they had potential to cut into Microsofts business. With that in mind, Gates then went on to outline a plan of attack to this threat, saying, “I want every product plan to try and go overboard on Internet features”.

In the following years, Gates waged a famous internet-browser war, in which he drowned out his competition and made Microsoft's product, Internet Explorer, the king of internet browsing. Although Microsoft's strategy for winning this war ultimately landed Gates in trouble with the FTC, for the time being, the commitment to responding to every challenger as a threat propelled Microsoft to dominance.

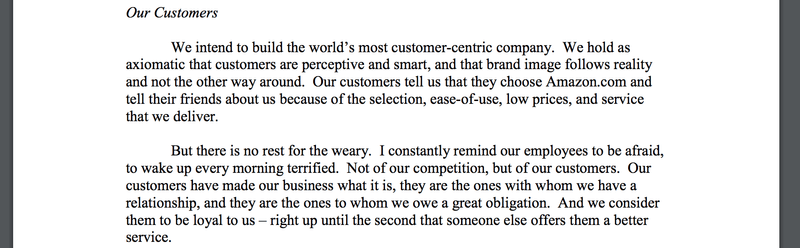

Comments from Jeff Bezos suggest that Amazon also grew on paranoia to a certain degree. In a 1999 shareholder letter, Bezos writes that he warns his employees to wake up terrified of customers because they could, at any moment, switch their loyalties to someone with a better service.

Although it sounds a bit extreme and fatalistic, this paranoia is, by all accounts, providing the right motivation to the Amazon team. Today, Amazon is synonymous with customer centricity and is consistently ranked as the top of customer-satisfaction reports.

Confrontational Management

A somewhat controversial element of Grove's management style was his proclivity for confrontation. Grove believed in the power of debate and conflict to refine and harden ideas into their most effective form. Every idea and proposal was meticulously picked apart and debated, with little regard for feelings, and Grove made sure to deter any laziness or low standard work by berating the offender. This management style is what landed Grove the title of “world's toughest boss” in 1984, but it's also what allowed him to get the highest standard of work out of his employees.

Since then, elite CEO's such as Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk have followed suit: pressing tough standards on their employees and, while sometimes at the cost of looking like jerks, ultimately producing the best possible products because of it.

Before Grove started publishing his books, his confrontational style was something of an urban legend, leaking out through stories of his severity from Intel employees. One Intel employee described meetings with Grove like “going to the dentist and not getting Novocaine. If you went into a meeting, you’d better have your data; you’d better have your opinion; and if you can’t defend your opinion, you have no right to be there.” Other stories that leaked out to the world contained vignettes of the CEO yelling and slamming his fists on the table.

Grove confirmed these stories as fact in Only The Paranoid Survive when he discussed the importance of debates in making managers decisions easier. “Debates are like the process through which a photographer sharpens the contrast when developing a print,” Grove writes. “The clearer the images that result permit management to make a more informed—and more likely correct—call.”

When asked about the potentially hostile work environment this commitment to debate could create, Grove said in an interview with the Chicago Tribune, “We encourage our people to deal with problems without flinching. At its best, the method means that people deal with each other very bluntly.”

This style of pushing employees and inciting debates made Grove a tough person to work for, but many employees acknowledge that he was demanding but also fair. He held himself to the same standards as everyone else and even sat in a cubicle like everyone else, indicating that his style really was about getting results rather than about flexing his CEO power privilege.

In the past decade, Steve Jobs was one of the more obvious examples of this confrontational management style. Jobs was known to fire employees in public meetings and resort to angry tirades to get his point across. Surely this sometimes bordered on irrational or even crossed the line and became too personal, but often it also led to the incredible innovation Apple became known for.

The first iteration of the iPod, for example, was too clunky for Jobs's taste. He told his engineers to make it smaller and slim it down. When they told him that would be impossible, he took the prototype they had been working on for months and dropped it into a fish tank. When bubbles came out, he pointed and said, “Those are air bubbles. That means there's space in there. Make it smaller.”

In the end, they came up with smaller and slimmer prototypes until, eventually, the first iPod, which became a staple Apple product and sold over 300 million units by 2011.

Steve Jobs might have been one of the more extreme cases of confrontational CEO's, but he was far from being alone in the tech world.

When presented with work that doesn't live up to his high standards, Jeff Bezos is known to go on the attack, reportedly rebuking other executives with comments like the following:

- “Are you lazy or just incompetent?”

- “We need to apply some human intelligence to this problem.”

- “This document was clearly written by the B team. Can someone get me the A team document? I don't want to waste my time with the B team document.”

“Amazon’s culture is notoriously confrontational,” writes Brad Stone, author of the Bezos-profiling The Everything Store, “and it begins with Bezos, who believes that truth shakes out when ideas and perspectives are banged against each other.”

One of the core principles at Amazon—as enshrined in Amazon's 14 leadership principles—is to “have backbone; disagree and commit.”

According to Stone, Bezos despises the idea that coworkers should always try to get along and maintain strong social bonds. “He’d rather his minions battle it out backed by numbers and passion,” Stone writes.

The best way to avoid an unpleasant confrontation at Amazon is to make your proposals and ideas as thoroughly thought-out and airtight as possible so you can defend them against criticism. Without the threat of ridicule, it's not likely that the CEO of Amazon Web Services, Andy Jassy, would have written 31 drafts of his idea proposal for Amazon Web Services before presenting it to Bezos. While you can argue with his methods, it's hard to argue with the success of AWS today, which generated over $25B in revenue in 2018 alone.

“To the amazement and irritation of employees,” Stone adds, “Bezos’s criticisms are almost always on target.”

Embracing Risk And Change

Entrepreneurs today pride themselves on building “nimble” companies and taking risks to carry out successful “pivots.” Andy Grove was one of the original proponents of this mind-set, and his writing is one of the main reasons it has become such a commonplace philosophy among startups. In his book Only The Paranoid Survive, Grove laid out the logical framework for embracing risk and how doing so will help you adapt and change your business. This framework gained credibility through the years as CEOs like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Bill Gates have embraced it to great effect.

The biggest pivot in Intel's history was their exit from the memory-chip industry and entry into microprocessors. In hindsight, this decision to switch to microprocessors was the obvious choice. At the time, however, the decision jeopardized Intel's entire foundation and made a lot of other executives and board members uneasy. The thought process behind Grove's decision became a core lesson of Only the Paranoid Survive.

“I learned how small and helpless you feel when facing a force that’s '10X' larger than what you are accustomed to,” Grove wrote, “I experienced the confusion that engulfs you when something fundamental changes in the business, and I felt the frustration that comes when the things that worked for you in the past no longer do any good. …And I experienced the exhilaration that comes from a set-jawed commitment to a new direction, unsure as that may be.”

Making these risky decisions became a point of pride for Grove, and something he urged others to do as well. “Companies don't die because they are wrong,” Grove writes. “Most die because they don't commit themselves. They fritter away their valuable resources while attempting to make a decision. The greatest danger is in standing still.”

All companies need to change and evolve, and every decision about how to change comes with a degree of risk. By extension, an essential part of leadership, according to Grove, is embracing the risk of change and making these decisions quickly and confidently.

Since Grove put this theory into writing, many CEO's have followed suit and committed themselves to making risky decisions to move their companies into unchartered territories. When you look at leaders like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Bill Gates, you will notice that they never focus on just one product. They are always expanding the scope of their businesses and taking risks on new products.

In his first shareholder letter, Jeff Bezos outlined “bold rather than timid investment decisions” as a central principle of Amazon's business plan, and he also established his commitment to resisting complacency and embracing change with his “Day 1” mentality. Staying in “Day 1,” Bezos explained further in his 2016 shareholder letter, meant keeping “customer obsession, a skeptical view of proxies, the eager adoption of external trends, and high-velocity decision making”. The resulting company culture was one in which risk-taking was acceptable in pursuit of innovation and change.

Bill Gates was also outspoken about the importance of risk and change in business. He famously noted, “To win big, sometimes you need to take big risks.” For Microsoft, that meant expanding their product offerings and their functionality constantly. In an interview with BBC, Gates cited this constant adaptation as a competitive advantage, noting that the companies Microsoft beat out were “one-product wonders” and that “they did not think about tools or efficiency. They would therefore do one product, but would not renew it to get it to the next generation.”

When it comes to embracing risk and change, however, Elon Musk is an unparalleled example of what Grove preached. After Musk's first major success in creating PayPal, he easily could have hedged his bets and lived off of that money for the remainder of his career. Instead, he put his neck on the line again and again to start companies as ambitious and risky as SpaceX and Tesla.

In 2008, Musk invested every cent he had made from PayPal into Tesla and SpaceX, both of which were on the brink of failure. For the next few months, Musk lived off loans from his friends, and his entire personal fortune rested on the success of two companies that were both attempting to do things that no other company had ever done. This decision fit into Musks's ethos, however, as he is known to say, “It's OK to have your eggs in one basket as long as you control what happens to that basket.”

Musk's gamble paid off as both companies were able to stay afloat and grow into established, successful companies in their respective industries. A further indication of the CEO's commitment to risk is his insistence on always expanding his companies into new areas.

Even as far back as 2006 when Tesla was still struggling to succeed in the automotive industry, Musk was openly setting his sights on moving into more industries and expanding the company's products. In a letter to the public announcing his “Master Plan,” Musk wrote that Tesla would be more than just cars. Tesla's purpose was “to help expedite the move from a mine-and-burn hydrocarbon economy towards a solar electric economy.” This meant that in addition to high-end sports cars, Tesla would eventually shift focus to affordable family cars and even expand outside the world of automobiles to build solar-powered home batteries.

By 2016, Tesla had built itself a strong foothold in the automotive industry, so Musk followed through with another piece of his Master Plan and acquired SolarCity for $2.8 billion so that they could begin building and selling solar home batteries. This move threw Tesla once more into a struggle to prove a largely untested concept and tied the company's success to the success or failure of a new investment.

To an outside observer watching Tesla succeed in making and selling electric cars, it might seem like an unnecessary risk to invest billions of dollars into a completely new product line when the company had only just started to succeed with its electric car manufacturing. But to Musk and other CEO's influenced by Grove, embracing the risks of realigning and transforming their businesses is absolutely essential and seen as a much better alternative than resting on past success.

A Lasting Legacy Starts With Great Writing

Andy Grove likely wasn't the first CEO to ever see the value of being a bit paranoid, of getting the most out of employees through confrontation, and of embracing risk and change. His value to current startup culture and current tech companies isn't necessarily that he invented these ideas; it's that he made them easily accessible to anyone who wanted to learn.

At the time Andy Grove was writing his books, he had built one of the most successful tech companies ever and had proved himself to be a smart and capable leader. Rather than holding onto the secrets of his success, though, he diverted from a lot of other CEOs of the past by putting all of his knowledge into writing and making it accessible to the wider world.

You didn't need to be a close confidant of Grove or work under him to learn from him, and you didn't need an MBA to understand his theories. Grove's ideas were explained clearly and simply enough for anyone to grasp, and as a result they spread like wildfire and worked their way into the cultures of upstart tech companies for years to come.