The Financial Benefits of Remote Work for Companies

Employees can save around $4,000/year working remotely. Do those savings transfer over to companies? Here's what the data says.

Remote work can save employees, on average, more than $4,000 a year. Remote workers spend less on commuting, lunches, and even work clothes.

Does that same cost-savings transfer over to the companies that employ these remote workers?

There are a lot of factors to consider, of course. But data and use cases suggest that yes, companies that do employ a remote workforce do see a positive impact on their bottom line.

Global Workplace Analytics estimates that a company can save $11,000 for every part-time remote employee. These savings can be attributed to:

- Real estate and operating cost savings

- Reduced turnover and absenteeism

- Productivity increase

A fourth factor that can contribute to savings is salary adjustments based on cost of living. In fact, localizing salaries based on cost of living is the primary reason many companies pursue hiring remote workers.

Real estate and operating cost savings

One of the easiest ways to see the impact of remote work on business owners is to look at where costs are lowered — including real estate. When more people work from home, companies need smaller office spaces to house essential personnel.

Ctrip, China’s largest travel agency, saved almost $2,000 annually per employee on rent by reducing the amount of HQ office space after offering telework options.

PGI estimates the average real-estate savings for companies with full-time remote employees to be $10,000 per employee per year.

You can see these savings in action with well-known companies that offered flexible work policies:

- Aetna shed 2.7 million square feet of office space, resulting in a savings of $78 million per year.

- IBM reduced its real estate costs by $50 million.

- McKesson has saved $2 million per year in its real estate costs.

Not all companies will see this type of savings. Companies headquartered in tech and financial hubs like New York and San Francisco have significantly higher rent expenses than companies in smaller urban areas.

But lower costs connected to a remote work policy go beyond rent:

- Relocation costs: Nortel estimates it saves an average of $100,000 per employee in relocation costs.

- Operating costs: Remote employees also reduce the costs associated with electricity, heating and air conditioning, and other expenses that keep an office running.

- Payroll costs: A 2017 study found that the average worker would accept an 8% pay cut for the option to work from home.

Reduced turnover and absenteeism

Turnover decreases by 50% when companies offer a work-from-home option, according to Scott Mautz, a former Procter & Gamble executive. Stanford Professor Nicholas Bloom came to a similar conclusion with his famed 2-year study on remote work and productivity — employee attrition decreased by 50% for remote workers in his study.

But why?

More than 80% of respondents to OWL Labs’ 2019 State of Remote Work report state that remote work makes them feel more trusted at work, less stressed, and more empowered to achieve an ideal work-life balance.

And it just so happens that being trusted, feeling less stressed, and having greater work-life balance equates to happier employees.

No commute

The lack of a commute, alone, can make employees happier and healthier. The average one-way commute time in the U.S. is 26 minutes, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That adds up to nearly nine days per year commuting. That’s time spent in a car — possibly in stressful traffic jams — rather than with family, for example.

Commuting length can impact health as well, which impacts happiness, productivity — and employer insurance costs.

A study published in 2012 found that individuals with commutes of at least 15 miles were less active and more likely to be overweight. And a commute of just 10 miles was associated with an increase in high blood pressure.

Reduction in unscheduled absences

Having a better work-life balance doesn’t just make employees happier. It also reduces the need for employees to take time off to take care of personal tasks. Nearly 80% of employees who call in sick aren’t sick. They call in sick to attend to family obligations, personal needs, or because they’re stressed.

These unscheduled absences cost employers between $1,800 and $3,600 per employee.

Realizing this, the American Management Association established a flexible telework policy. As a result, they reduced unscheduled absences by 63% per employee.

Productivity increase of remote workers

Managers often worry that remote employees work less or multitask between personal responsibilities and their work.

Data shows the opposite.

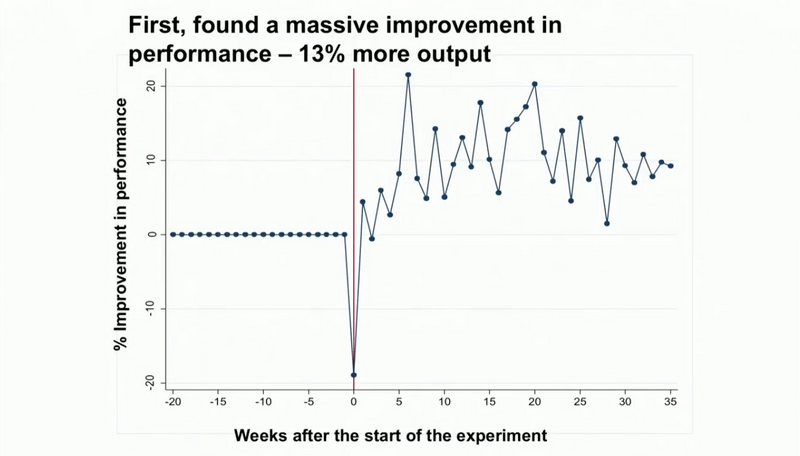

Bloom’s two-year study revealed that remote workers were 13% more productive than their office counterparts.

Employee happiness plays a part in productivity. But it’s not the only factor.

Bloom cited two contributing factors to his findings:

Remote employees worked more than employees in the office.

Remote workers don’t show up late to work because of a traffic jam. They’re also less likely to take excessive coffee breaks — many don’t take lunch breaks. Remote workers are also able to run errands and schedule appointments without losing a full or even half-day of work.

The typical office environment is far more distracting than folks realize.

Some workers thrive in an office environment. But not everyone does. It would be nearly impossible — and incredibly expensive — for a company to construct an office that catered to the preferences of all their employees.

Remote workers, on the other hand, can easily create their ideal workspace. They can work from anywhere. If, for example, they’re distracted at home, they can drive to a coffee shop for a few hours (assuming there aren’t any wi-fi network security concerns or, of course, a pandemic like COVID-19 that shutters most commerce).

“When you stop and you look at the data available to us, in almost two-thirds of the cases, every leader that granted the work-from-home option has found productivity has increased by as much as 50%.” — Scott Mautz

Boosting productivity across your org

Some managers fear that allowing employees to work from home could negatively affect communication and collaboration. However, that’s only the case if teams try to make remote teams communicate synchronously.

It’s generally more efficient to communicate with remote workers asynchronously (email, documentation, Slack). As a result, remote-friendly companies benefit when they embrace asynchronous communication.

A culture of asynchronous communication cuts down on unnecessary conversations and meetings. If a point can be made in an email, it will be. If an idea can be pitched in a written memo, it should be. Asynchronous teams communicate more efficiently and clearly. When a meeting is required, teams can use a video conferencing tool like Zoom or Skype.

Salary adjustments based on cost of living

The average 1-bedroom apartment in San Francisco rents for $3,411, while a similar-sized apartment in Raleigh, NC, is $1,177.

Employers who hire within cities like San Francisco and New York City account for this increased cost of living with higher salaries.

For example, according to Glassdoor, the average salary for a Product Manager based in Raleigh is $104,976, while in San Francisco, it’s $129,387.

Hiring remote workers allows companies to retain a headquarters in tech and financial hubs like S.F. while expanding their talent pool to areas of the country (and world) with a lower cost of living. The result? Companies can save on salaries by hiring remote employees who live in more affordable regions, then localizing their salaries based on their cost of living.

GitLab has a publicly available database of “location factors” that adjust salaries from its San Francisco baseline. Buffer uses data from Numbeo to group their teammates into one of three geographic bands (high, average, and low-cost) by comparing the cost of living index of a teammate’s location to the cost of living index in San Francisco. Someone who lives in a low-cost region is likely to be paid less than someone with the same title who lives in a high-cost region.

Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg recently announced that remote work would soon be an option for both new and current employees — but that salary adjustments would apply.

Other remote-friendly companies shun the approach.

Basecamp, a 100% remote company, pays “everyone as though they live in San Francisco and work for a software company that pays in the top 10% of that market,” its founder David Heinemeier Hansson wrote. “San Francisco was our benchmark because it’s the highest in the world for technology, and because we could afford it, after carefully growing a profitable software business for 15 years.”

If you plan to adjust salaries based on cost of living, you won’t be alone. But you will want to be prepared for any potential personnel conflicts that arise from variances in salaries of employees with similar roles. Being upfront with your salary localization policy, like GitLab and Buffer, will help.

You’ll also want to be aware that there are companies (like Basecamp and many SF-based startups) that don’t localize salaries. By offering high-paying salaries regardless of location, these companies may seem more attractive to top talent.

Factoring in the expenses of remote working

There are expenses connected to remote work. For example, are face-to-face interactions an essential part of your company culture? Then you’ll likely be responsible for the airfare and room and board of your remote team.

Remote workers need access to company software and data, as well. And companies need to address how to provide technical support to their remote teams.

Also, remote employees still need internet access, a desk, and a computer. They still eat lunch and drink coffee. Some employees want to work at a coworking space — it’s the next best thing to being in the office. An integral part of any remote work policy is an equivalency code: If you offer perks to office workers, you should find an equivalent perk to provide remote employees. This prevents remote employees from feeling like second-class citizens.

But most companies don’t reimburse or cover these costs for their remote workers. 75% of respondents to Buffer’s 2019 State of Remote Work study said their company does not pay for home internet, and 71% said their company does not cover the cost of a coworking membership.

As remote work becomes more prevalent, a larger number of companies will be competing to attract this diverse talent pool. Those companies that offer to pay for certain expenses of remote workers (like internet access, coworking memberships, and coffee) will have an easier time attracting top talent. And even after factoring in these expenses, remote workers likely still save companies money.

Why some companies are hesitant to hire remote workers

Few things are absolute. While countless companies have saved money by hiring a remote workforce, not every company will experience those same savings.

But the potential expense (or lack thereof) is not even what stops most companies from hiring remote workers. Here’s what does:

- The misconception that productivity will take a hit. As noted earlier, the data does not support this claim.

- Leaders feel more managerial when they can see their employees. It’s easier to feel more like a leader when your employees are within sight.

- Lack of imagination. Many leaders assume that some roles in their organization can’t be done remotely. More often than not, they’re wrong.

Often, the decision to hire remote workers doesn’t come down to economics. It comes down to culture. Once you and your team are culturally ready to embrace a remote mindset, data suggests you’ll be better off financially — and productively.