We Analyzed How 38 CEOs Send Emails—Here's What We Found

A well-crafted email can inspire investors and teammates. See how other CEOs use the power of emails to their advantage.

With the decentralization of the startup economy and the increasing prevalence of remote and distributed teams, clear, asynchronous communication has never been a more important skill for executives to master.

This is evident with the rise of team wikis and tools like Slack. Still, email—the oldest and most durable of the digital communications tools we have—has lost none of its importance.

With potential partners, the way you email (or don't) can help you close or lose deals. With your team, it sets the tone. And with your investors, it can either inspire confidence or questions.

Finding a Method to Maximize Productivity

One of the traits that most differentiates great CEOs is their decisiveness—and their ability to recognize when to act fast.

“You can always course-correct if things don’t work out,” the CEO of Alibaba, Daniel Zhang, wrote. “The real fear is in the state of paralysis that results when you can’t make a decision at all.”

What Amazon’s Jeff Bezos calls “high-velocity decision-making” relies upon the realization that, in most cases, even a bad decision is better than making no decision at all.

Great CEOs apply this mentality to their email inboxes with ruthless efficiency, responding to emails at lightning speed, avoiding over-communication, and setting clear expectations for the people they interact with.

1. CEOs Reply to Emails Immediately

A lot of CEOs respond to their emails as soon as they see them. As former Google executive Eric Schmidt wrote, “there are people who can be relied upon to respond promptly to emails, and those who can't. Strive to be one of the former. Most of the best—and busiest—people we know act quickly on their emails, not just for a select few senders, but to everyone.” Even when Schmidt doesn't have a clear response or answer to an email, he makes sure to send a confirmation of receipt saying “got it,” so he can move on to the next thing without keeping the sender wondering or waiting.

A promise from Warren Buffett's 1982 shareholder letter.

Time kills deals, so the CEO who is quick to see a good offer is usually quick to snatch it up. As Warren Buffett knew, establishing a reputation for emailing back quickly sends a message to co-workers and potential customers that you're always at work, eager to work with others, and don't shy away from unpleasant but necessary challenges.

2. They Send Fewer Emails to Receive Fewer Emails

While a lot of CEOs are known to respond to emails quickly, they are not often the most active emailers in their company. CEOs need to be accessible but cannot be constantly weighed down by email.

Karl Iagnemma, the CEO of nuTonomy, sends no more than 25 emails a day because spending any more time than that on email means he is taking time away from more important tasks.

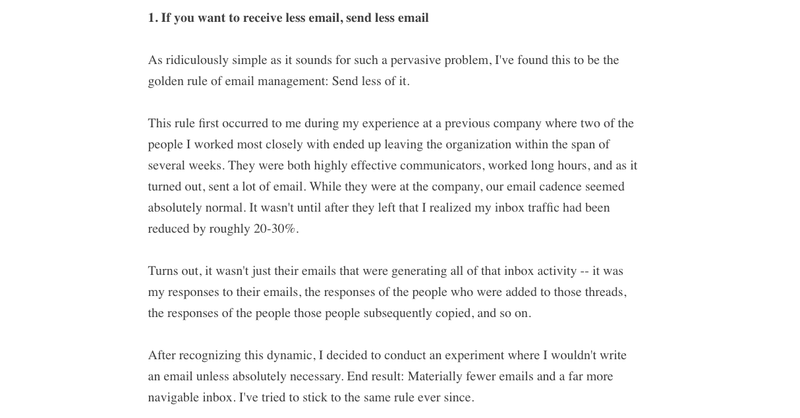

Jeff Weiner, the CEO of LinkedIn, has a similar practice. His began after two high-profile communicators he worked with at a previous company left, and he suddenly realized that his inbox volume had dropped by 30%.

It wasn't simply their emails that were creating so much activity for Weiner to respond to—it was the cascading effect of replies and responses that each email created.

While they worked hard and communicated well, their flurries of activity created exponential growth in the amount of messages that Weiner and his other teammates needed to respond to—collateral damage caused by the structure of email itself.

3. They Are Clear With Expectations

A lot of CEOs also cut down on the amount of time they need to spend processing and interpreting the emails they receive by being upfront with the people they work with about what they expect in an email.

Katia Beauchamp, CEO of Birchbox, is a perfect example of this. To help her prioritize her inbox and quickly process which emails are most urgent vs. less urgent, she insists that her employees include a specific time they need a response by. Instead of wasting time and energy trying to infer from the content of the emails which ones are most urgent and forming priorities from there, she front-loads that work onto the sender.

Mark Cuban makes his inbox more predictable by instructing the people he works with on how frequently they should email him and what they should email him about. In a blog post about working with Cuban after Shark Tank, the founders of Guardian Kids Bikes explain that Cuban expects a weekly email letting him know what advice or help they need and where they are struggling in a short, concise manner.

As the co-founder Brian Riley writes: “We only send him questions that we are really struggling with, like a strategy question of going this way or that way. We keep our emails as concise as we can, without going into the weeds too much”...“If he can get email updates from us every week and have a pattern of our condition and what’s going on, it enables him to give really great advice.” Consistent and predictable content allows Cuban to minimize the time spent on understanding the context or purpose of the emails he receives.

Using the Right Language to Send the Right Message

The effectiveness of an email largely comes down to how it is interpreted. As a result, CEOs are very deliberate about using the right words—or lack thereof—to create the desired effect. Interestingly, they often use common techniques in wording and phrasing.

4. They Say 'We' Instead of 'I'

In an interview published in the New York Times, Jonathan M. Tisch, co-chairman of the Loews Corporation, cited one of the most important lessons he has learned in his years of doing business to be “never start a paragraph with the word 'I,' because that immediately sends a message that you are more important than the person that you’re communicating with.”

In looking through emails from CEOs to their employees, it seems that most leaders agree on the power of using collective pronouns like “we” and “us” and “our.”

In a 184-word email Philippe von Borries, the co-CEO of Refinery29, sent to his employees after Donald Trump was elected president, the word “We” appeared eight times and began three out of the five paragraphs. In a pivotal moment in the email, von Borries writes, “This is a moment for us to rally together, to be even more ambitious in the impact we can have, to produce our best work. We are a company in which we can live our passion and move our collective mission forward every day.”

The use of the words “we” and “us” in this example helps employees see themselves as part of a supportive community rather than an individual within a company. If you look through emails and letters from CEOs, you will see a lot of “Our mission,” “Our code of conduct,” and “We are making progress” phrases because these phrases spread ownership of goals and achievements to everyone, making them feel like a part of something important.

In 2015, Satya Nadella sent an email to Microsoft employees discussing the company's strategic plan for the coming years. To help his employees feel more invested in this plan, he uses “we” and “our” to make the wider company feel included. “I believe that we can do magical things when we come together with a shared mission,” he writes. “Our mission is to empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more.”

5. CEOs Use Brief, Standardized Responses

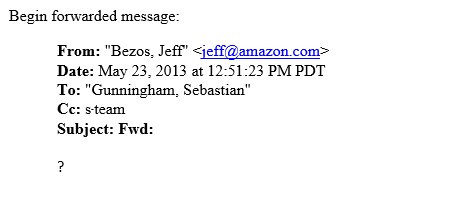

CEOs are notorious for sending brief, standardized responses to emails and know exactly how to get their point across as quickly and succinctly as possible. Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are the most extreme, and maybe the best, examples of this.

An Amazon customer who emailed Jeff Bezos directly receives a response from a member of the Tech Support Executive Customer Relations team “on behalf” of Bezos himself.

Whenever Jeff Bezos sees a concerning email from a customer, he forwards the email to the person in charge of the department at fault with nothing added to the email but a question mark. Bezos explained further in an interview that the question mark is “shorthand for, 'can you look into this?' 'why is this happening?'” Elon Musk uses almost the same tactic except, instead of a question mark, he uses the three-letter acronym WTF. Both approaches reportedly send the recipient into an all-out scramble to right the problem and report back.

6. They Put an Emphasis on Empathy

While the examples above seem a bit curt, CEOs also know how to make their emails more empathetic, and they often use language to communicate empathy and understanding. This is a much-needed skill for CEOs, especially when they need to address something particularly unpleasant that happened in the company.

In the spring of 2018, a high-ranking employee at Netflix was fired for using offensive language on more than one occasion. To acknowledge the situation, Reed Hastings, the CEO, wrote an email to employees reassuring them that the company's values do not line up with that type of behavior, and it will not be tolerated.

After explaining the situation, Hastings writes, “As I reflect on this, at this first incident, I should have done more to use it as a learning moment for everyone at Netflix about how painful and ugly that word is, and that it should not be used.”

After accepting a piece of the blame himself and acknowledging the harm it caused, he also goes on to empathize with the people who worked closely with the fired employee: “Many of us have worked closely with Jonathan for a long time, and have mixed emotions.” Hastings then ends the email with another sentence reassuring and supporting the employees who were most affected by the fired employee's actions by saying, “Unfortunately, his lack of judgment in this area was too big for him to remain. We care deeply about our employees feeling safe and supported at Netflix.”

By writing with an extra emphasis on communicating empathy, Hastings prevented the situation from snowballing into widespread discomfort and distrust throughout the company.

Content Specific to the Function of a CEO

In addition to commonalities in email management methods and language, CEO emails often touch on the same themes and messages. As the visionary leaders of their companies, CEOs are responsible for creating a narrative around the company's mission and values, as well as responses to any threats to those missions and values. As a result, the content of many of their emails tends to skew towards these larger concepts and to confronting threats to these ideas.

7. They Start With the Bad News First

When a direct threat to a company's well-being presents itself, there is no use in avoiding it or tiptoeing around it. CEOs instead prefer to confront problems head-on.

In 2015, the New York Times published an article that painted a very hostile picture of the work culture at Amazon. Knowing that this was a widely read and high-profile piece with the potential to turn the perception of Amazon, both externally and internally, for the worse, Bezos wrote an email to employees responding to the threat.

Instead of tiptoeing around the purpose of the email, Bezos starts off by providing a link to the article and encouraging his employees to read it. He then goes on to write, “Here’s why I’m writing you. The NYT article prominently features anecdotes describing shockingly callous management practices, including people being treated without empathy while enduring family tragedies and serious health problems.”

After getting the bad news out of the way, Bezos uses the rest of the letter to make his case that the article is more fiction than fact and that he is committed to creating a healthy and productive workplace culture. The very act of confronting the bad news head-on showed employees that the threat could not be all that credible as the CEO had no hesitation in bringing it up and talking about it.

8. They Always Talk About Customers

A common theme in CEO emails is an insistence on prioritizing customers above all else.

Take Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft. In a 2018 email announcing two new engineering teams and the reasons behind creating the new teams, Nadella writes, “Having a deep sense of customers’ unmet and unarticulated needs must drive our innovation. We can’t let any organizational boundaries get in the way of innovation for our customers.”

In an email to Deutsche Bank employees announcing himself as the new CEO, Christian Sewing also focused the content of his email on customer needs when he wrote, “We should focus less on ourselves and more on our clients. They are our reason to be. And our approach should be to offer them convincing solutions and not just products. If we add value for our clients, we deserve our share of it – but only then.”

CEOs have more power and influence over creating a narrative around the company's values and larger-picture priorities than anyone else in the company, so it is common to see them focus on ideas like customer centricity in their emails.

9. They Bring Crisis & Failure Back to the Mission

Most businesses experience setbacks in their growth and significant failures, which force leadership to make tough decisions. This often comes to a head with an announcement about large-scale layoffs or cutbacks. It's an announcement that employees dread receiving and CEOs dread giving. However, many CEOs also use such announcements as an opportunity to bind the team closer together by putting the layoffs and cutbacks in the framework of a larger picture of success.

In 2016, Brian Krzanich, the CEO of Intel, announced they would need to lay off 12,000 employees in the coming months. After announcing the news and thanking all the employees who will be laid off for the work they have done for the company, Krzanich goes on to write, “Today’s announcement is about accelerating our growth strategy. And it’s about driving long-term change to further establish Intel as the leader for the smart, connected world.”

By bringing the focus back to how the decision to cut 12,000 jobs fits into the larger mission, the CEO frames a negative event as a step forward.

Leading Through Email

The “CEO style” of emailing has become a well-known and widely adopted trope: terse declarations, short responses, and often cryptic messages that leave the recipient struggling to interpret the point.

In reality, the ways that CEOs email are diverse and varied, though there are similarities across the board: generally quick response time and high decisiveness when communicating with the outside world, systematic efficiency when communicating inside the team, and a customer-first mentality when writing (implicitly or explicitly) for the wider public.

Even as Slack and other similar tools rise to earn a greater share of the intracompany communications market, email (with its universality and familiarity) is likely to remain—at least for CEOs and those they communicate with—the most important communications medium out there.