Empowering Your Team to Regulate Their Emotions at Work

The most challenging problems managers struggle with are tied to emotions. Teaching your team how to regulate emotions will help.

Many companies strive to cultivate a culture where emotions are anything but volatile. Having an even-keeled demeanor is seen as a formula for cohesiveness. Even-keeled teammates don’t lash out at colleagues. They don’t create a hostile workplace.

But an even-keeled demeanor does not come naturally to everyone.

Humans are emotional. We get anxious at an impending deadline. We get angry when someone critiques our work. We get stressed when stuck in traffic, then we bring that stress into the office.

The most challenging problems managers and executives struggle with are tied to emotions, according to Rachel Green, Director of the Emotional Intelligence Institute of Australia.

“The technical problems can be solved,” Green says. “But the people problems are the hardest to deal with.”

Managing these “people problems” requires empowering your team to learn how to regulate their emotions — so that they can respond to any scenario at work in a constructive, positive manner.

The power of emotion regulation

Knee-jerk reactions can lead to adverse outcomes. If you’ve raised your voice, snapped at a colleague, or hammered away an angry Slack message, you’ve experienced how challenging regulating your emotions can be.

Our need to react is a primal response that occurs when our amygdala, which regulates fight or flight, is triggered.

While some people are naturally gifted at resisting the urge to “fight,” others are not. Fortunately, the power to pause and reflect — rather than react — can be learned. Recognizing that you can choose how to respond to something, despite how you feel, is the foundation of emotion regulation.

“When we buy time, we then have access to the frontal lobes of our brains, where we have access to reasoning, better problem solving and perspective,” explains Dr. Kris Lee in her 2018 book Mentalligence: A New Psychology of Thinking: Learn What it Takes to be More Agile, Mindful and Connected in Today’s World. “We never have to take the bait of primitive emotions.”

Your upstairs brain vs. your downstairs brain

J.J. Gross, in his 2015 Handbook of Emotion Regulation, defines emotion regulation as “the process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express these emotions.”

In other words, emotion regulation empowers you to know what you’re feeling and what to do about it in any environment. It can influence:

- The type of emotion you experience

- The intensity of that emotion

- When the emotion starts (and how long it lasts)

- How you express that emotion

None of this is possible until you identify your emotions. Author and psychologist Dan Siegel refers to this as the need to name it to tame it.

To understand the effect of name it to tame it, consider this simple analogy Siegel uses:

You have an upstairs brain — or cortex — where you do all your thinking and planning. You also have a downstairs brain (subcortical), responsible for emotions, motivation, and the fight or flight response.

Your downstairs brain becomes active when you feel a specific emotion, like anxiety or fear. This reptilian part of your brain cannot reason through this emotion. Its job is to assess the scenario in an instant and tell your body to fight or leave.

But you have control over this instinct. By simply identifying (and naming) the emotion you’re feeling, you trigger your upstairs brain — the part of your brain that does use reason.

According to Siegel, studies show that when you name the emotion your downstairs brain generates, your upstairs brain will pass “soothing neurotransmitters” to the downstairs brain to calm it down.

When the instinct to react is kept at bay, you have the opportunity to pause, reflect, and choose how to respond to what you’re feeling.

This name it to tame it strategy is a common theme in each of the four branches of the widely referenced Mayer-Salovey Four Branch Model of Emotional Intelligence.

Mayer-Salovey Four Branch Model of Emotional Intelligence

The four branches of the Mayer-Salovey Four Branch Model of Emotional Intelligence are:

- Perception, Appraisal, and Expression of Emotion

- Emotional Facilitation of Thinking

- Understanding and Analyzing Emotions; Employing Emotional Knowledge

- Reflective Regulation of Emotions to Promote Emotional and Intellectual Growth

These four branches are arranged in order of complexity. The lowest level branch (Perception, Appraisal, and Expression of Emotion) focuses on more basic skills — the ability to perceive and express emotion. People who struggle to control their emotions should start here.

The highest level branch focuses on a more complex skill: the conscious, reflective regulation of emotion. People who are naturally inclined to control their emotions will find an easier time achieving this higher-level branch.

It is possible to progress through each branch to evolve into a highly emotionally intelligent person — someone who can regulate their emotions and use them to better themselves and others.

Below we break down each branch. When reading the first three sections, keep in mind the following scenario:

Your boss emails you to express disappointment in a project you spent a considerable amount of time on. Your body tenses. Your heartbeat quickens. You’ve clicked ‘reply’ to the email and are ready to respond...

1. Perception, Appraisal, and Expression of Emotion

This is your ability to identify and label specific feelings in yourself and others — just like Siegel’s name it to tame it example.

But this branch takes things one step further. Not only is it important to label emotions to control them. You have to be able (and willing) to discuss these emotions.

Using our workplace scenario above: You recognize that your tense body and hastened heartbeat are symptoms of getting upset. You explicitly say out loud, “I feel upset right now.”

Rather than immediately reply to your boss to defend your work, you reach out to a trusted colleague and share how you feel. This gives you enough time to tamper down your emotions and respond to your boss in a non-confrontational tone.

Tip: You don’t have to discuss your emotions with a colleague, or anyone else. You can also express your emotions in writing that you don’t share with anyone — meaning explicitly write out that you feel angry, for example. Often this is the most productive path to take.

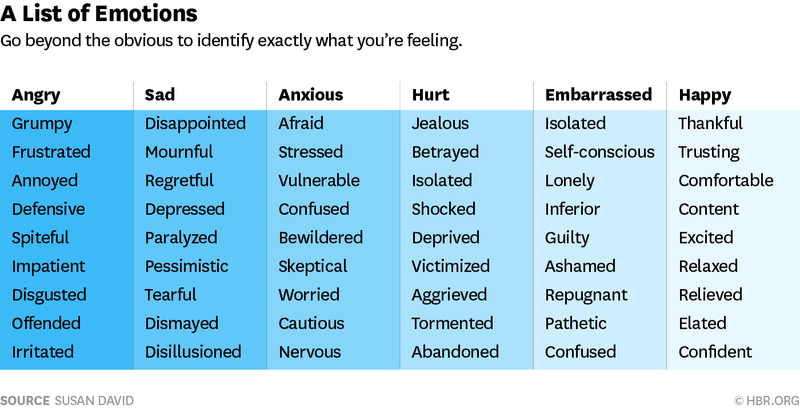

Also, having a list of emotions on hand can make it easier for you to identify how you feel. Use this list below, courtesy of Harvard Business Review, for reference:

2. Emotional Facilitation of Thinking

This is the ability to use your feelings constructively; to let these emotions guide you to what is most important for you to think about.

Using our workplace scenario, while sharing your emotions (whether with a colleague or in writing), you try to understand your boss’s perspective.

Effective communication occurs when you can empathize with your audience. What was your boss’s expectation of the finished project? Where, in her eyes, did you fall short?

When we react on impulse, we don’t give ourselves enough time to separate our emotions from the bigger picture. We fail to consider others’ needs. But when you pause, identify your feelings, and connect your emotions to the bigger picture, you’re more likely to offer solutions in your response to your boss — and not merely an emotional defense.

3. Understanding and Analyzing Emotions; Employing Emotional Knowledge

This is the ability to understand the meanings of emotions and how they can change. Those who achieve this level of emotional intelligence understand how emotions are connected to our basic psychological needs.

Using our workplace scenario, you not only recognize that you’re getting upset. You can identify why you feel this way. Your boss’s approval is important to you. To you, her disappointment in this one project equates to her disappointment in your overall contribution to the team. This leads you to question your value at work, which leads you to worry that your career is in jeopardy.

By processing all that, you’re able to take a step back and realize this is just one project. There are countless times when your boss sang your praises. This empowers you to respond to her with calm confidence, knowing you are more than capable of exceeding her expectations as you’ve done before.

Achieving this self-awareness equips you with the skills necessary to help others — which we discuss in step four below.

4. Reflective Regulation of Emotions to Promote Emotional and Intellectual Growth

This is the ability to turn negative emotions into growing opportunities and, specifically help others identify and benefit from their emotions.

For this section, let’s introduce a slight alteration to our scenario:

You and your colleague work together for two months on a project. After presenting your project, your department head expresses his disappointment in the outcome. Your body tenses. Your heartbeat quickens. You notice your colleague looks as tense as you feel...

First, it’s important to accept that you can’t help others until you help yourself. It’s why flight attendants instruct you to put your oxygen mask on first. And it’s why this — the final branch— is considered the most challenging to achieve. You need to be the master of your domain before you can empower others to master their own emotions.

After identifying you feel upset, you understand that the only person responsible for you feeling that way is you. It was not your department head’s intention to upset you — he does not have that much control over you. No one does.

This puts you in control of the situation. Rather than respond to your department head immediately, you ask if you and your colleague could take the afternoon to reconvene. You do this because you know your colleague is still in fight-or-flight mode. His “upstairs brain” has not triggered. Removing him from the situation eliminates the potential of him lashing out at your department head, causing irreparable harm.

Because you’re capable of identifying your emotions and understanding why you feel how you feel, you are able to help your colleague walk through the necessary steps — starting with name it to tame it. You help him see your department head’s critique isn’t personal. It’s just one isolated incident.

Then, you ask your colleague to put himself in your department head’s shoes. What was he expecting from the project? Where could you do better? What can you do that would surprise and delight your department head?

Now, by the time you and your colleague respond to your department head’s criticisms, you have an action plan in place to improve the project — and buy-in from your colleague.

The common thread: learn how to react on your own terms

Your team is likely made up of people with varying degrees of emotional intelligence. Regardless of one’s emotional intelligence, the commonality here is the ability to react with intention.

But reacting on your own terms doesn’t just occur because you simply held your tongue for a few moments. If you want to improve how you respond to specific workplace scenarios – regardless of how you feel — you need to rehearse your desired reactions. For example,

- How would you like to react to a stressful situation?

- What would you prefer to say when confronted with an idea you don’t like or agree with?

Encourage your team to create a personal response document for how they want to respond to common workplace scenarios. It’s particularly effective if these documents incorporate each employee’s unique triggers.

For example, Dotty in HR gets annoyed when someone misuses the general Slack channel. Her response document should include a script for how she would prefer to respond to her colleagues when they misuse Slack.

“Research shows we are capable of building a positive emotional repertoire and redirecting our energies to help us from being stuck in negative emotional states.” — Dr. Kris Lee

Just remember, before you can respond on your terms, you need to pause long enough to name and tame your emotions.

Creating an environment that fosters emotional regulation

1. Asynchronous communication

There is a growing number of remote and distributed teams in the workforce. At the same time, there’s a push for these teams to embrace synchronous communication through tools like Slack and Zoom. Synchronous communication can be useful — sometimes. Real-time conversations help teammates brainstorm and build camaraderie.

However, synchronous communication also makes it harder for people to practice control over their emotions.

As a distributed and remote-friendly team, we here at Slab have embraced an asynchronous culture. We share and respond to critical knowledge inside Slab — and use Slack for ephemeral topics.

But asynchronous communication isn’t reserved for remote and distributed teams. Centralized teams can benefit from it as well. It’s challenging to work through the steps of the Mayer-Salovey Four Branch Model of Emotional Intelligence in a real-time conversation. Shifting communication to channels such as email (and even Slack, when used as an asynchronous channel) can empower your team to practice the skills necessary to become highly emotionally intelligent.

You can learn more about our approach to asynchronous communication, as well as tips on how to create a healthy Slack etiquette guide in our article, Creating a Slack Etiquette Guide for Your Workplace.

2. User manuals

Many teams — including ours — have teammates write a user manual. These manuals, or user guides, help colleagues know what makes each of us tick (and what makes us lose our mind). There is no formal template to creating a user manual — although we’re particular to the approach by Chris Blachut.

We also think it’s a good idea to add those personal response document scripts discussed earlier inside these user manuals.

These manuals can empower teammates to identify colleagues’ triggers and steer their teammates to their desired responses, rather than knee-jerk reactions.

For example, if you notice the tone of Dawn’s voice becoming a little sharp after a conference call, her user manual is a useful tool to help her pause, reflect, and choose her desired response.

Emotions are unavoidable — but manageable

As complicated as we make emotions to be, they are little more than energy built up inside our bodies. This energy seeks some type of release — in the form of expression.

We all have a choice: We can let our “downstairs brain” dictate how we respond to our emotions, or we can trigger our reason-driven upstairs brain, and set forth a series of events that leave us empowered by our emotions — rather than at their mercy.

By simply naming how you feel, you take responsibility for your emotions and make it more likely that regardless of how you feel, you can make the most out of any scenario.