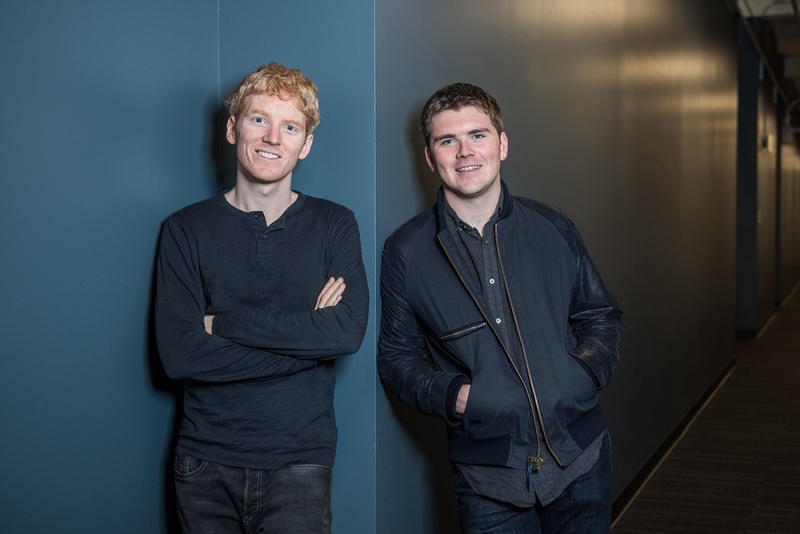

How Stripe Built a Writing Culture

Stripe’s Documentation Manager shares how the company built a culture where writing is second nature.

For a company whose product focuses on numbers, Stripe has built an enviable writing culture.

Their quarterly software engineering magazine (Increment) and publishing imprint (Stripe Press) are impressive on their own. But it’s Stripe’s internal writing culture that differentiates the company. Whether it’s an email to a colleague or a memo to an entire team, Stripe employees strive to write with excellence.

Their strong writing culture benefits the organization in several areas:

- Time efficiency. Sharing ideas through writing eliminates the need for repetitive verbal updates to disseminate ideas and information.

- Knowledge sharing. Documenting important ideas forces clarity of thought and makes information more accessible to everyone in the company, versus slide decks that are ephemeral and require less rigor of thought.

- Communication. Clear writing requires clear thinking, meaning employees invest more time shaping their ideas before sharing them.

“Writing forces you to structure your thoughts in a manner just not possible when you verbalize it. When I write, I have to offer structured, precise thoughts.”

The result is that Stripe’s internal and external documentation is a central pillar of the company’s reputation and brand.

How did this happen? We sat down with Stripe’s Documentation Manager, Dave Nunez, to learn more about what it takes to build a strong writing culture.

Leaders must demonstrate quality writing

Getting employees to write more frequently shouldn’t be your ultimate goal. Getting them to write more proficiently should be.

One of the most effective ways to encourage proficient writing is to demonstrate it.

“The first emails I saw from our CEO [Patrick Collison] literally had footnotes,” Nunez recalls. “He structured his emails to be like research papers and put the peripheral information at the bottom so as not to detract from the core information.”

Today, footnotes are a common component of internal emails at Stripe. The CEO set the expectation; employees strive to uphold it. But Collison’s approach to writing did more than demonstrate the value of a footnote. It’s understood that at Stripe:

- Writing matters. Make it count.

- Everyone’s time is valuable. Make the effort to put together coherent ideas in writing.

- The clearer the writing, the clearer your message and intent will be.

Collison isn’t alone in his passion for quality writing. The modus operandi for leadership communications across Stripe is carefully structured narrative documents and emails. You’re far more likely to read a narrative memo during a Stripe project kickoff meeting than to sit through a PowerPoint presentation.

“From leadership on down, we default to writing,” Nunez said. “We don’t really have slide decks.”

How can you lead by example to foster a writing culture? Here are two ideas inspired by the Stripe playbook.

1. Exemplify quality writing in everything you and your leadership team share.

Footnotes might not be right for every company, but strategies anyone can adopt include citing reputable sources, being economical with your words, and ensuring your writing is free from grammar and spelling errors.

As a leader, consider having someone else review your writing for clarity and readability — then let your team know you had your writing reviewed. This transparency showcases just how committed you are to increasing the impact of your words.

“You wouldn’t ship code without having it reviewed; your words are just as important,” says Nunez.

2. Make writing the default method of sharing knowledge.

Eschew slide decks for narrative memos. Share new ideas through carefully crafted emails.

When an employee pitches an idea to you, ask them to expand on it in writing.

Show them you value the effort required to convey one’s thoughts into writing by explicitly granting them the time necessary to think through and process their thoughts into writing.

“I’m only a month into my time at Stripe, but I’ve never encountered a tech company of this size where writing is such a center of gravity.”

Give teammates a starting point with sample docs

Nunez and his team create sample docs that other teams can use as inspiration for their own documents.

For example, his team published a detailed guide on the life of a Stripe charge. They walked through every step of the process, from the point of sale with the customer, to the back end, bank transactions, and more.

While the content itself was specific to a Stripe charge, the document serves as a valuable reference to other teams on how to write a guide. Teams use this document to understand what type of language to use, to see what types of visuals are most effective, and to learn how to structure their writing for better comprehension (such as when and where to use subheads and lists).

Stripe has similar sample docs for READMEs, runbooks, and FAQs. Nunez believes these sample documents are more useful than fill-in-the-blank templates, because they provide readers more context and content to work with.

“We create docs that offer some of the basics, so engineers aren’t forced to stare at a blank page — which can be terrifying,” Nunez says.

Not every company has a dedicated documentation department. But creating sample documents doesn’t have to be an arduous task. Identify the types of documents most teams would want to produce — then have your most proficient writers create ambitious documents that can be later used as reference documents.

Know when to standardize and when to give autonomy

Standardizing how your team documents shared knowledge ensures content is easy to understand and streamlines the writing process.

But it’s neither scalable nor empowering to standardize everything.

It’s not scalable because it would take constant oversight to ensure every document met a specific format. Few companies have (or are willing to invest in) the resources for this kind of oversight.

It’s not empowering because what works for one team won’t necessarily work for another. Standardizing your entire documentation process robs teams of creating an experience that works best for them.

Stripe toes the line between control and autonomy by establishing a standardized approach for high-leverage documents only — those with a broader audience (like a document intended for multiple teams) or significant implications (like if it impacts business operations).

This approach ensures that the most widely read information receives the oversight it deserves, while teams still maintain autonomy over how they document knowledge most pertinent to them.

In contrast, each team at Stripe has far greater control over the look and feel of documents with a smaller audience and impact.

Standardization at Stripe isn’t represented by a series of templates employees plop their knowledge into like Mad Libs. Rather, standardization at Stripe is more about ensuring the clarity of the content and the reading experience live up to the company standard of quality writing. To ensure this, Nunez typically gets his team involved in reviewing these high-leverage documents before they’re shared.

Replicating this process is straightforward — establish criteria that differentiate high-leverage documents from low-leverage ones. For example, you could define high-leverage documents as:

- Intended to be read by three or more teams

- Contains information that will go unchanged for at least one year

- Will impact general business operations

Documents designated as high-leverage should either follow a specific format, be reviewed by a dedicated team before publication, or both.

Make your documentation easy to read

The point of documenting something is to get others to read it. Without active readers inside your company, your writing culture will never flourish.

So, how do you get people to read what you wrote?

“I think the visual aspect is super important,” Nunez says, “because the first impression tells someone whether the content is approachable or not.”

A visually appealing document doesn’t always contain images and graphics. Nunez has seen beautiful documents that contain no visuals at all.

“You can look at the document and see, ok, this is super simple,” he says. “The intro is very short, there’s bulleted lists down here, and it just gets to the point.”

But, he admits, that’s rare. Visuals and diagrams simplify documents. They make them more approachable, which is why he suggests whenever you can replace text with diagrams, do it.

Diagrams or not, everyone on your team should consider the visual aspect of their writing. Here are a few items to consider:

- Keep paragraphs short (3–4 sentences). If possible, make the first paragraph of a document 2–3 sentences.

- Use subheads and bulleted lists to break up walls of text.

- Consider your audience when writing. Some audiences value complex words — some don’t. The goal is to find the most compelling language for the audience you need to reach and act on your document.

- Edit frequently. Edit your own work, and ask peers to edit it as well. Editing is the key to getting the best clarification of your idea.

Create a support system

Writing well is not supposed to be easy. Writing well requires more critical thinking (than, say, speaking off the cuff), which produces better results.

The payoff is worth the effort, which is why everyone on your team should strive to be strong writers.

However, sometimes the writing process can create significant barriers that prevent team members from ever sharing their ideas.

Employees who struggle with writing, or whose native language isn’t English, may feel less confident contributing their knowledge.

Nunez has seen this throughout his career — he worries that a company does itself a disservice when some employees don’t feel empowered to share their ideas in a writing-heavy environment.

To address this, he emphasizes the importance of onboarding classes for new hires focused on writing and documentation, as well as office hours, and self-service resources. This demystifies the documentation process — but it also emphasizes just how important documentation is to business operations from the outset.

One thing Nunez is starting to experiment with is pairing ESL employees with writing mentors. He’s done this informally over his career, but would love to see companies create more formal programs for writing mentorships.

“The idea here is that you come with your writing, and a judgment-free expert writer will help you as if they were your college English professor,’” Nunez says.

But even your team’s strongest writers need support. Nunez, for example, is the first to admit that his writing can become long-winded and confusing. So, he regularly shares his work with a handful of colleagues he trusts to offer kind but honest feedback.

Many others across Stripe have colleagues review their work, as well.

“Engineers do this with their code,” he says, “and we do it with our writing.”

Building your culture of writing and documentation

When your CEO uses footnotes in his email and your company publishes full-length books, it’s clear that writing matters.

But you don’t have to be Stripe to develop a culture that embraces writing and documentation. Lead by example; know when to standardize internal writing and when not to; make your documents easy to read; develop a support system that encourages and empowers everyone to write. These are the building blocks from which any company can build a culture where writing and documentation become second nature.